Mortality Data

Patients with PK Deficiency have a significantly higher probability of death1,2

Study Design

- A retrospective cohort study assessed mortality using data from CPRD linked to the HES database and ONS in the United Kingdom1

- Patients of all ages with PK deficiency were eligible for study inclusion if they had ≥1 PK deficiency diagnosis code in CPRD1

- 89 patients with PK deficiency who met the inclusion criteria were matched 1:5 with 445 non-PK deficiency controls1

- Controls with no PK deficiency and no acquired/congenital anemia codes were matched using exact matching without replacement to patients with PK deficiency based on birth year, sex, and availability of medical records1

- The median (range) age at index was 20 (0-74) years for the PK deficiency cohort and 20 (0-74) years for people without PK deficiency3

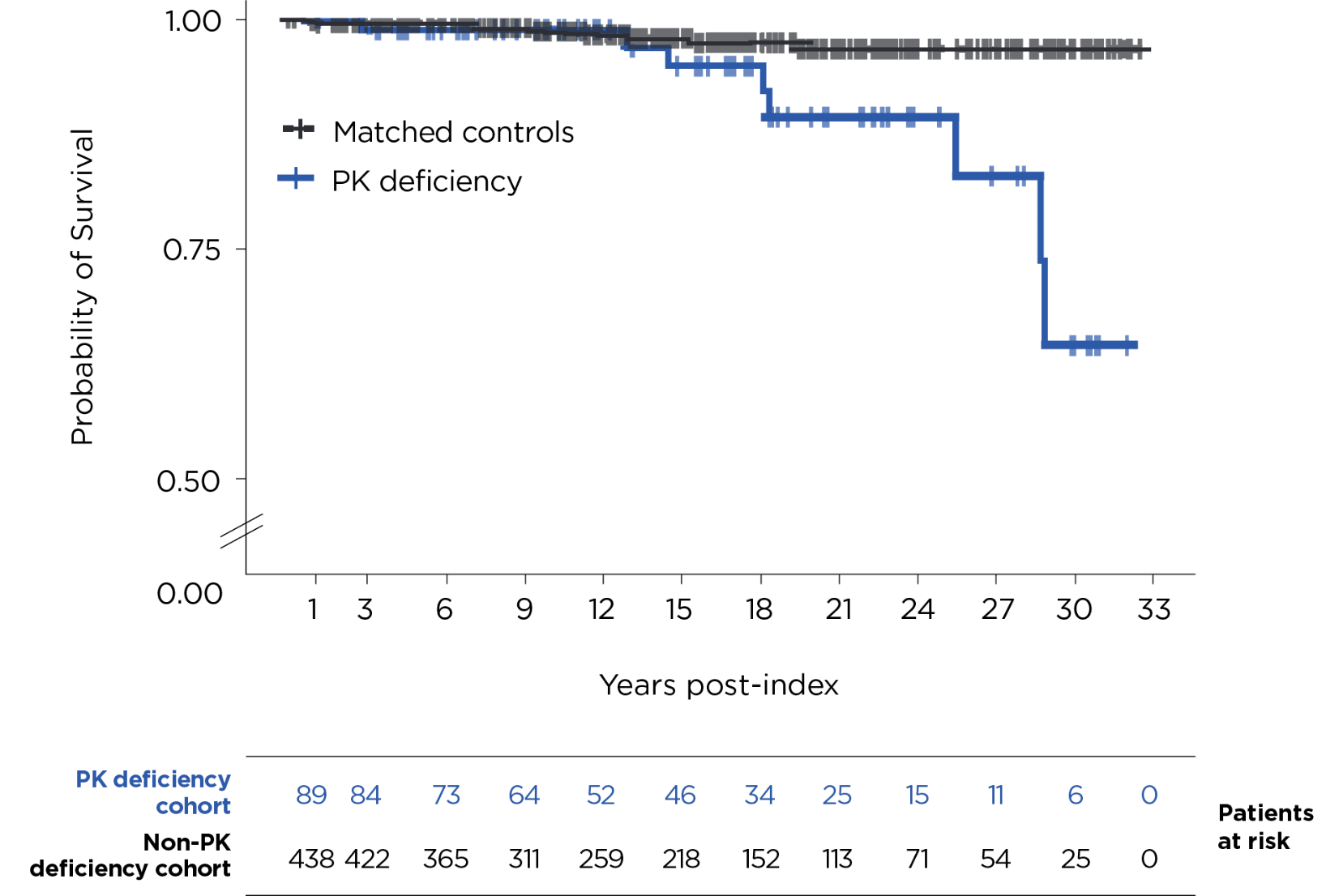

Probability of Survival

Kaplan-Meier analysis of time from first recorded diagnosis to death in patients with PK deficiency vs time from medical record dated the same year as the PK deficiency patient’s diagnosis to death in the matched comparison cohort.1

Patients with PK deficiency had a numerically higher frequency of iron overload than matched controls (16% vs <1%), 26% of patients with PK deficiency had a record of gallstones and 21% had received a cholecystectomy, whilst this was 2.5% and 1.6% for matched controls, respectively. Matching date for matched controls was the first medical record in the same calendar year as the first diagnosis code for patients with PK deficiency.1,3

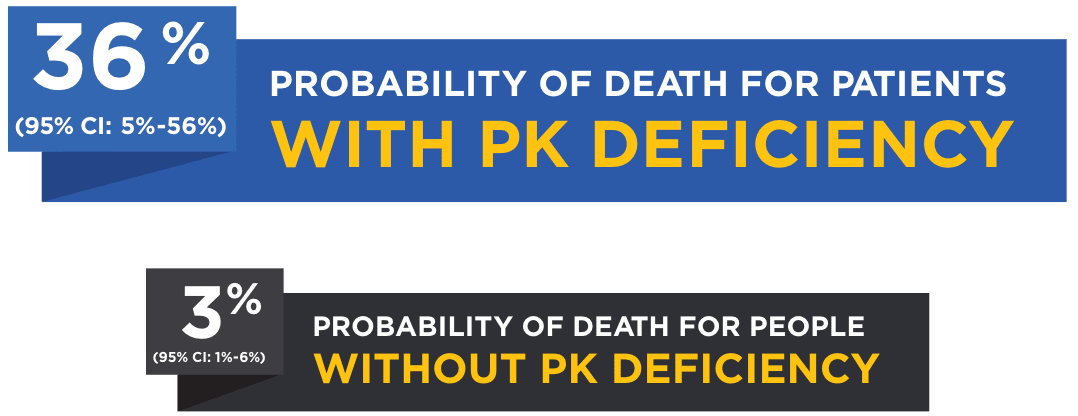

Probability of Death

30 years after index1:

Probability of death (95% CI) at 15 years was 5% (0%-11%) for patients with PK deficiency and 2% (1%-4%) for people without PK deficiency.1

The index date was based on the first occurrence of a PK deficiency diagnosis code; however, actual diagnosis of PK deficiency may have occurred prior to appearance in the databases used for this analysis. Due to General Data Protection Regulations and small sample size, causes of death are not reported. Due to the unavailability of genetic test results, this study was unable to confirm the diagnosis of PK deficiency or distinguish hereditary and acquired PK deficiency.1

During the follow-up period,* 8/89 patients (9%) in the PK deficiency group died, while 9/445 (2%) in the control group died.1

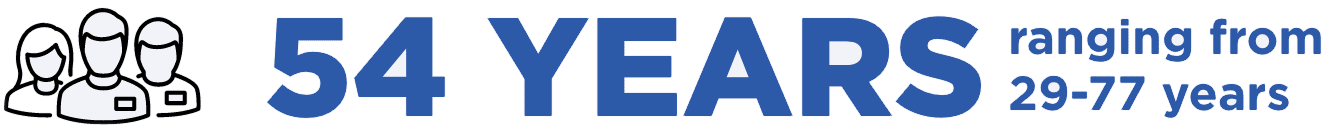

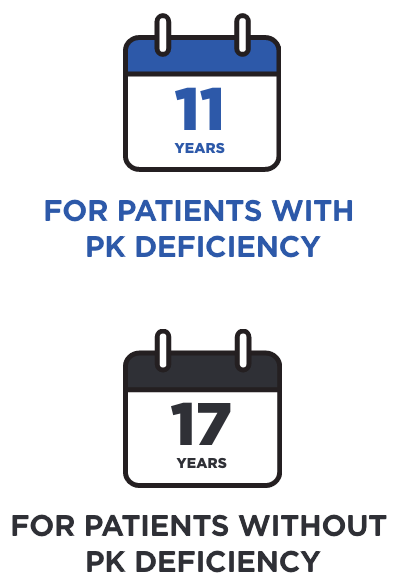

In this study, the median age at death among patients with PK deficiency was3:

CI=confidence interval; CPRD=Clinical Practice Research Datalink; HES=Hospital Episode Statistics; ONS=Office of National Statistics.

*The follow-up is the time in years from matching date until death or censoring. Censoring was defined as the earliest of de-registration from the practice, last data collection from practice/hospital, or the end date of the study (October 31, 2020).1

Study Design

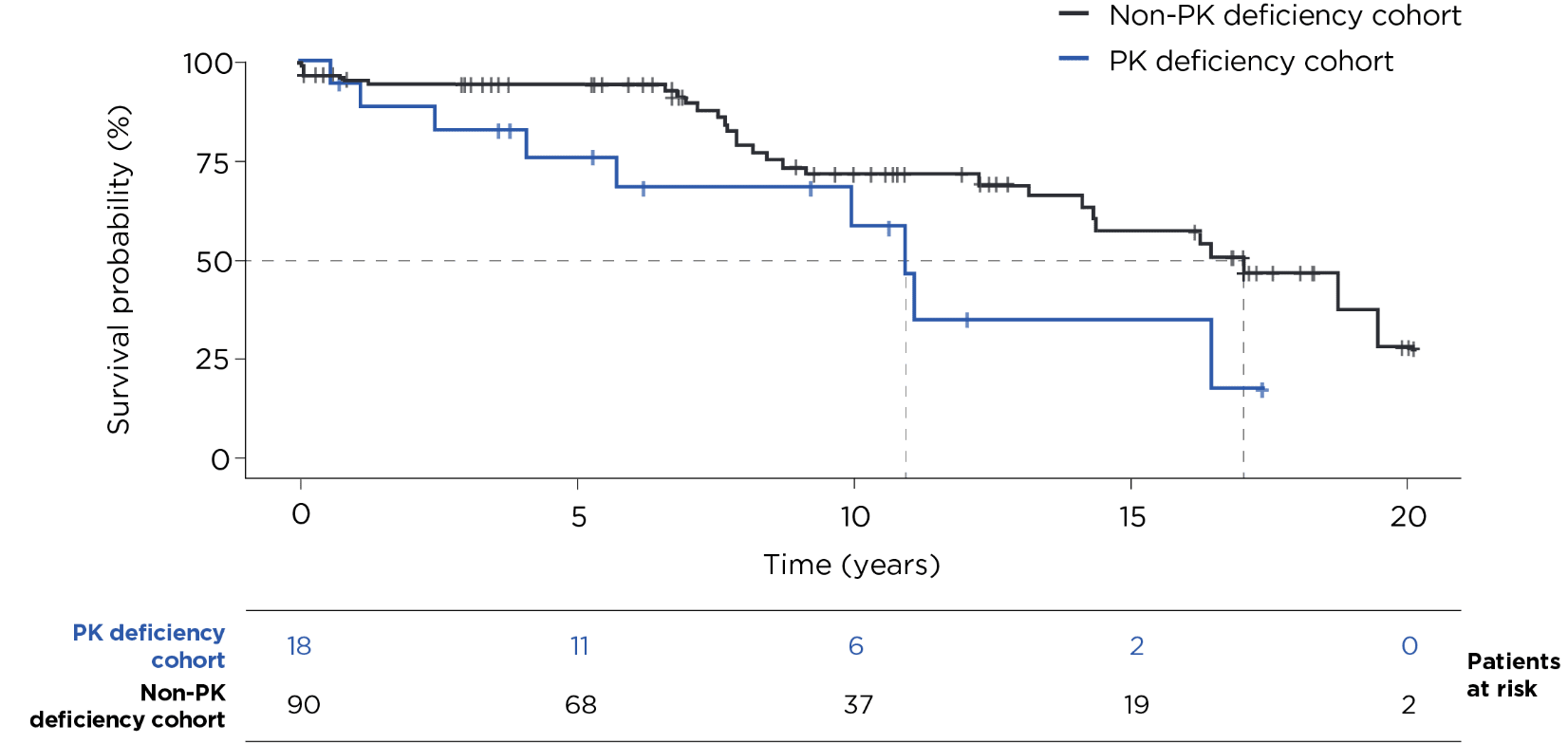

- Using data from the US Veterans Health Administration (VHA), 18 patients with PK deficiency were matched 1:5 by age, sex, and index year (+/- 1 year) to 90 individuals from the general US VHA population with no diagnosis codes related to PK deficiency2

- The index date for the PK deficiency cohort was defined as the date of the first medical record with a diagnosis code related to PK deficiency2

- The index date for the non-PK deficiency cohort was defined as a random visit date during the index year of their match2

- Overall survival was compared between the PK deficiency cohort and the non-PK deficiency cohort2

- For both cohorts, the median age at index was 59 years2

- There were no significant differences between cohorts by age, sex, race, or mean Charlson Comorbidity Index2

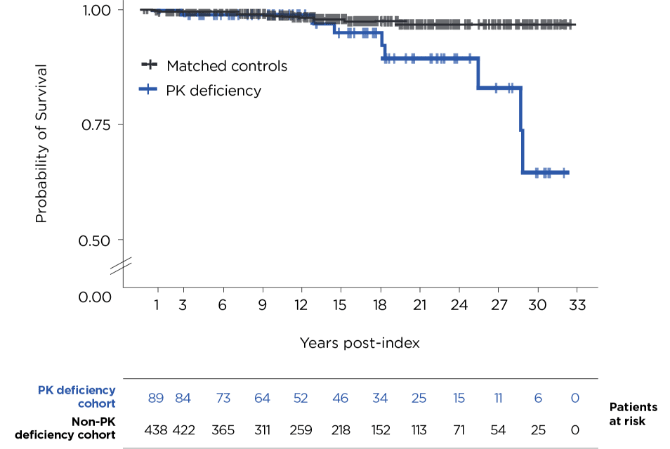

Probability of Survival

Kaplan-Meier results were compared using a univariate Cox proportional hazards model with robust standard error estimation.

As female, pediatric, and adolescent populations are underrepresented in this study, the results may not be generalizable. Due to the unavailability of genetic test results, this study was unable to confirm the diagnosis of PK deficiency or distinguish hereditary and acquired PK deficiency.2

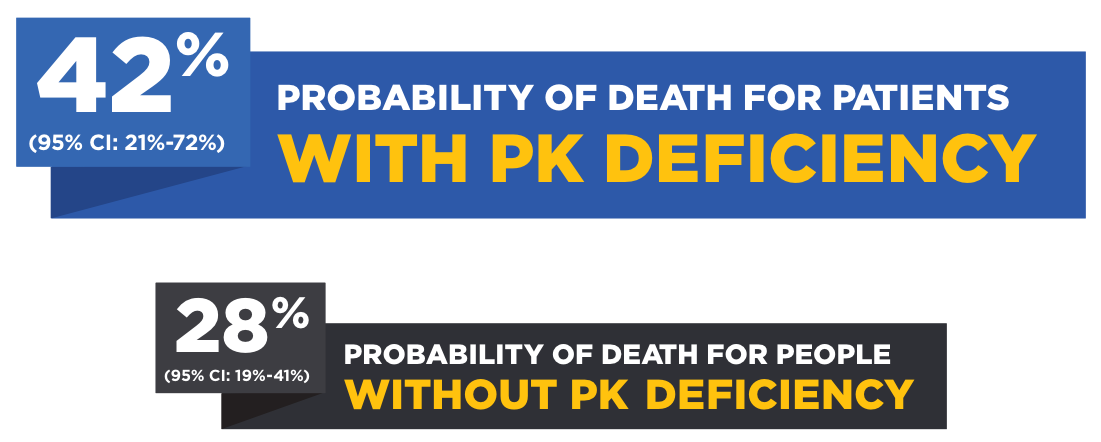

Probability of Death

10 years after index2,3:

Median years until death after index2:

The cause of death for patients in this study varied.

These studies were sponsored by Agios Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

NEW

MORE ON THE MORTALITY DATA

References: 1. Higa S, Keapoletswe K, Cirneanu L, et al. The clinical characteristics and overall survival of patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency in the UK: a real-world study. Presented at: European Hematology Association (EHA) Hybrid Congress; June 8-11, 2023; Frankfurt, Germany, and Virtual. 2. Zagadailov E, Boscoe AN, Garcia-Horton V, et al. Mortality among veterans with a diagnosis of pyruvate kinase deficiency: a real-world study using US Veterans Health Administration data. Presented at: European Hematology Association (EHA) Virtual Congress; June 9-17, 2021. 3. Data on file. Agios Pharmaceuticals, Inc.